talking to Philips Hue lights, part 2: industrial design

Okay, so last time, I wrote about connecting to my lights. This time, I’m going to write about what I actually did to put my code to use. It’s all well and good to have a working library to control the lights, but I was going to need a way to actually cause useful network calls to be made.

Starting off, I had to figure out what I actually wanted to be able to do. My primary goal was simple: I wanted to have an easy way to toggle my lights between at least a couple settings:

- normal warm lighting, to use most of the time

- dim light for reading my Kindle or other relaxed activity

- much cooler light, which (for reasons I don’t understand) makes me look less awful on Zoom

- some goofy settings for being goofy

I don’t want you to get the idea that I’m incredibly vain. I don’t think I spend much time thinking about how I look, but in mid-2020, I was on Zoom all the time, and I was literally distracted by the my terrible color. It sometimes helped if I closed all the white-background windows on my desktop, but this wasn’t really an option. Just look at this horribleness (warm light on the left, cold light on the right):

Now that you understand how pressing a matter this was, let’s talk about specifics.

a program to control the lights

Remember how, last time, I said the API was boring and like every other API?

That’s still true. So talking about the program itself isn’t very interesting.

I do want to write a more interesting program and tie this into the Wink LED

server I wrote, but I haven’t and

honestly it’s hardly a high priority. Anyway, the little program is called

(right now) lights and looks like this:

use v5.30.0;

use warnings;

my $address = q{...};

my $username = q{...};

use Future;

use IO::Async;

use IO::Async::Loop;

use IO::Socket::SSL qw( SSL_VERIFY_NONE );

use JSON::MaybeXS;

use Net::Async::HTTP;

sub rgb_to_xy {

# described in previous post

}

my $loop = IO::Async::Loop->new;

my $http = Net::Async::HTTP->new(

SSL_verify_mode => SSL_VERIFY_NONE,

);

$loop->add($http);

my $res = $http->do_request(

uri => "http://$address/api/$username/groups"

)->get;

die "Couldn't get groups!\n" unless $res->is_success;

my $json = $res->decoded_content(charset => 'undef');

my $data = JSON::MaybeXS->new->decode($json);

my ($office) = grep {; $_->{name} eq 'Office' } values %$data;

my @office_lights = $office->{lights}->@*;

my %set = (

bright => {

on => \1,

xy => [ 0.4574, 0.41 ],

bri => 254,

colormode => 'xy',

alert => "none",

effect => 'none',

},

# …and more presets…

);

die "no setting given\n" unless @ARGV;

die "unknown setting\n" unless $set{ $ARGV[0] };

my @do;

for my $id (@office_lights) {

push @do, $http->do_request(

method => 'PUT',

uri => "https://$address/api/$username/lights/$id/state",

content => JSON::MaybeXS->new->encode($set{$ARGV[0]}),

content_type => 'application/json',

)->then(sub {

my ($res) = @_;

warn "failed to update light $id\n" unless $res->is_success;

return Future->done;

});

}

Future->wait_all(@do)->get;

I will probably improve this code to make it use async/await and some other

mild conveniences, but it’s fine. So anyway, I can run lights bright and

it makes the lights bright. lights dim dims them. I have lights zoom.

You get the idea.

That program can run on any machine on the network, because it talks directly to the Hue bridge, so that’s sort of convenient, but I don’t want to have to open a shell and run a program to change my lighting. Even that is too much. For some other similar problems, I’d use Hammerspoon to give myself some little macOS menu bar item that would talk to the bridge (or some intermediary) when I clicked it. Here, though, that felt like too much. If I’m reading a book and want to turn the lights up, my computer might be asleep. It might be in the other room. I didn’t want to have to get it, open it, log in, or anything like that.

I tried using Siri for a little bit. There’s decent Siri integration, so I could say “Hey Siri, office lights dim”. That’s neat, but it’s slow. Sometimes it failed. Also, if the lights were dim and Gloria walked in and I wanted to turn the lights up, I’d have to ask her to wait while I talked to Siri. Unacceptable!

triggering the lights

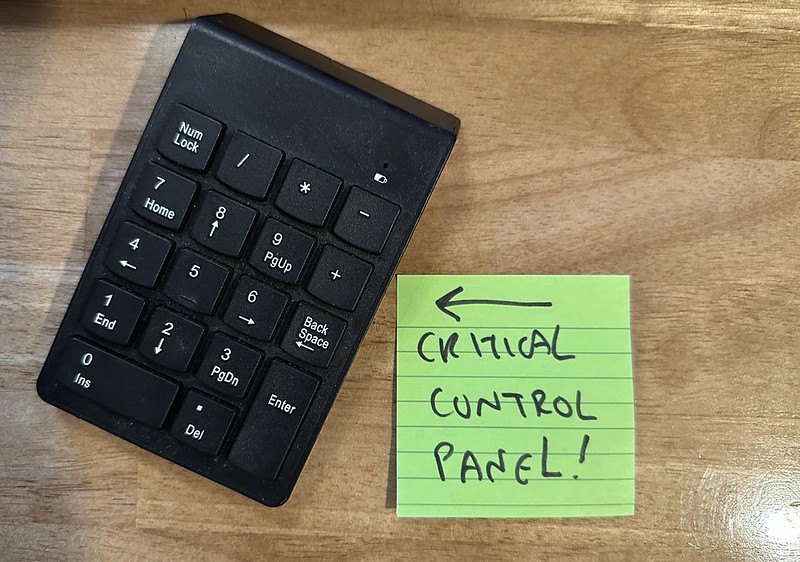

What I wanted was a light switch that could handle all my presets (and maybe more). There are “smart” light switches, but they didn’t really handle that. I looked into a bunch of hardware solutions and was at my wit’s end when a friend (I think it was Robert Spier) suggested I just get a cheap wireless numeric keypad. I bristled at the idea, because it didn’t seem very cool, but I liked that it seemed cheap and easy, so I got one.

It cost nine dollars and took a single AAA battery. That was cool, but now what? The idea was “push those buttons to change the lights”, but my next step was to make that happen, and I had no idea how to go about it. So, I read things on the Internet. I went down several blind alleys before finding Triggerhappy. There haven’t been any commits to the (seemingly) official Triggerhappy repository in years, so I’m concerned that it’s dead. Instead, though, I will choose to believe that it is complete as well as perfect.

Triggerhappy is a hotkey daemon. It runs in the background, monitoring input devices, and when it sees certain kinds of input it does stuff. Now my job was easy: tell it what to monitor, for what, and what to do when it saw the right thing. I installed Triggerhappy on the same Raspberry Pi that has my four blink(1) LEDs in it. That little box sits on my desk, mostly idle. I plugged in the keypad’s USB receiver and got Triggerhappy working.

I’m sorry to say that I don’t remember all the steps required. It didn’t “just work”, but it wasn’t too far off. I’ll find out, I guess, when I try porting this setup to the next box. In the end, it was mostly “let the default init script run”. That script runs this:

triggerhappy --daemon \

--triggers /etc/triggerhappy/triggers.d/ \

--socket /var/run/thd.socket \

--pidfile $PIDFILE \

--user nobody /dev/input/event*

I don’t think I customized that. At any rate, the key thing is the

triggers.d directory, which points to configuration for what triggers what.

My configuration is very, very simple:

KEY_ESC 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights off

KEY_KP0 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights off

KEY_F1 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights bright

KEY_KP1 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights bright

KEY_F2 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights dim

KEY_KP2 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights dim

KEY_F3 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights zoom

KEY_KP3 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights zoom

KEY_KPPLUS 1 /home/rjbs/bin/lights alert

That’s it. The 1 means the event fires on keydown. When the ESC key is

pressed, triggerhappy turns the lights off. You can do more complicated things

by acting on “key held down” or “three keys together”, but what do I need that

four? This numeric keypad only has eighteen keys.

Also, you’ll see that my invocation of triggerhappy includes

/dev/input/event*. I’ve got it listening to all event sources, which means

(among other things) “all hardware keyboards”. If I plug in a USB keyboard to

hack on this box and try to use Vim, I’ll be using Vim in the dark. But I

won’t! This is a little Raspberry Pi, and when I want to do things on it, I do

them over ssh.

The other good thing about settling on triggerhappy is that it’s not tied to my

lights. I can make the * button send a text message or the 7 button put on

some good music. I probably won’t, any time soon, but I could, and what

better comfort is there than the idea that we can easily do something we’ll

never really want to do?

what’s next?

I want to build a little web frontend to let me trigger presets from my laptop. Sure, I mostly won’t use it, but I can definitely see myself doing something with it via Hammerspoon, once I can. Also, I had it before, and used it to make an enormous industrial STOP button on my desk trigger an alarm sound and flashing red lights. I’d like to make that work again, just in case.

Really, though, my next step is to make this and a few other things easier to set up on a brand new box. Like I said above, I barely remember how I made it go the first time, which means if this box dies, I’ll be figuring it out again from first principles, with this blog post as my notes. Not great! I guess it may be time that I finally learn Ansible.