so many CPAN uploads! (code review mark iii)

Today, I uploaded 114 new versions of things to the CPAN. This is a lot, but none of them was very interesting. Mostly, I was updating my email address or adding some documentation about what Perl I plan to worry about in future releases. In some cases, there were typo or bug fixes. I thought I’d just write a little bit about this, from “why” to “how” to “how but another kind of how”.

Why bother?

Honestly, not a terrible question. Many of the things I uploaded today hadn’t been updated in around ten years, and for those even today’s update wasn’t much of an update at all. Sometimes it’s because the code already on the CPAN works and doesn’t need any changes, and sometimes it’s because the code never really got used by anybody but me (if that) and so its bugs were undiscovered or don’t need fixing. So, why update things?

What if I just want to cut my losses? What could I do then?

I could delete the code from the CPAN, but this seems sort of risky. What if somebody was using it and it goes away. I don’t think I was thinking about deleting anything obviously in much use, but you never know what’s being used. Every once in a while I find out something I thought was totally ignored has been doing work for somebody else for years. Deleting things from the CPAN seems a bit antisocial, anyway.

I could just stop thinking about the code. It would sit there just like it

has, which is fine, I guess. But it all provides my cpan.org email address,

which I set to bounce, earlier this year. The story for “I want to abandon

this code” on CPAN isn’t great. The bugtracker and repository come from the

distribution metadata, which will stay there after you walk away, and they’ll

be pointing at your bugtracker. Or you can make a new upload that has no

bugtracker and repo in the metadata. When you do that, though, people will be

directed to rt.cpan.org, which will send new tickets to the cpan.org address of

the last uploader. I’ve whinged about this in the past, so I’ll just leave it

with: it’s hard to walk away cleanly.

What you can do, though, is mark the library as up for adoption, by giving permissions to the fake PAUSE user “ADOPTME”. I did that for a bunch of things I don’t plan to touch again, but I still wanted to get the email updated.

Anyway, then there’s code that basically works, and I might tweak in the future, but has mostly been untouched for ages. Almost all my older code targeted perl v5.8, because for ages, that was just the done thing. These days, worrying about any Perl older than, say v5.24 is just a total drag. I want to make clear to anybody using my code what version of Perl I’ll limit myself to over time. I do that with a Dist::Zilla plugin that adds a bit of documentation like this:

This library should run on perls released even a long time ago. It should work on any version of perl released in the last five years.

Although it may work on older versions of perl, no guarantee is made that the minimum required version will not be increased. The version may be increased for any reason, and there is no promise that patches will be accepted to lower the minimum required perl.

There are a few different pieces of boilerplate like that. The one quoted above is for the policy I call “long-term”. I want to get these sections into released code as soon as possible, to give as much heads-up as possible. (In reality, I’m not sure it matters. If it had been there from day one, there would still be complaints when someday I bumped up the version. Still, it seems like the right thing to do.)

So, are these reasons good enough to do all these uploads? Oh, heck, I don’t know. But I decided they were, at least if it was easy enough. Fortunately, it’s easy enough.

How’d I make it easy?

Well, first off, I use Dist::Zilla! The whole reason I wrote Dist::Zilla in the first place was to make it easy to release things easily without having to do much work. This was a great case for it.

What I had to do for any given repo was basically:

- rename the default branch at GitHub to

main - do some cleanup of my local GitHub repo

- update my email address in

dist.ini - add a

perl-windowentry indist.inito get that policy text from above - add a

.mailmap, if needed - add a

.gitignoreentry for the cache file that the version-from-tag plugin uses - update the Changes file

- release!

Here’s the thing… Dist::Zilla mostly helps with step eight. The other ones are all sort of the work normally left to me, the human. I didn’t want to do that work one hundred fourteen times! So, I wrote a stupid little program:

#!/usr/bin/env perl

use v5.36.0;

system(qw( git branch -m main ));

warn "Couldn't move branch to be main\n" if $?;

system(qw( git remote rm origin ));

warn "Couldn't remove origin\n" if $?;

use IO::Async::Loop;

use Net::Async::HTTP;

use Path::Tiny;

use Process::Status;

my $http = Net::Async::HTTP->new;

IO::Async::Loop->new->add($http);

my $dir = path('.')->absolute->basename;

die "Can't compute repo name; what?!\n" unless $dir; #?!

my $res = $http->do_request(

method => 'POST',

uri => "https://api.github.com/repos/rjbs/$dir/branches/master/rename",

headers => [

Authorization => "token GITHUB-TOKEN-HERE",

],

content_type => 'application/json',

content => '{"new_name":"main"}',

)->get;

unless ($res->is_success) {

die "can't rename master to main on github: " . $res->as_string;

}

{

my $file = path('dist.ini');

die "no dist.ini" unless -e $file;

my @lines = $file->lines;

for (@lines) {

s/OLD-EMAIL-1/NEW-EMAIL/g;

s/OLD-EMAIL-2/NEW-EMAIL/g;

}

unless (grep { /perl-window/ } @lines) {

my ($i) = grep {; $lines[$_] eq "[\@RJBS]\n" } keys @lines;

splice @lines, $i+1, 0, "perl-window = long-term\n";

}

$file->spew(join q{}, @lines);

}

{

my $file = path('.gitignore');

die "no .gitignore" unless -e $file;

my @lines = $file->lines;

unless (grep { $_ eq ".gitnxtver_cache\n" } @lines) {

push @lines, ".gitnxtver_cache\n";

}

$file->spew(join q{}, sort @lines);

}

MAILMAP: {

my $file = path('.mailmap');

last MAILMAP if -e $file;

$file->spew("Ricardo Signes <NEW-EMAIL> <OLD-EMAIL>\n");

}

{

my $file = path('Changes');

die "no Changes" unless -e $file;

my @lines = $file->lines;

my ($i) = grep {; $lines[$_] eq "{{\$NEXT}}\n" } keys @lines;

splice @lines, $i+1, 0, <<~'END';

- update packaging and metadata

- minimum required Perl is now v5.12

END

$file->spew(join q{}, @lines);

}

# kind of iffy; but I never have local hooks, right?

system(qw( rm -rf .git/hooks ));

Process::Status->assert_ok("removing git hooks");

system(qw( git add Changes .mailmap .gitignore dist.ini ));

Process::Status->assert_ok("staging files");

system(qw( git commit -m ), 'auto-preparation of updated release of ancient code');

With that program, my human-operated steps became:

- chdir to my repo for any project in need of an update

- run that program

- review what it did (because once in a while it did something stupid)

- release!

Not bad. But “any project in need of an update” carries with it the secret tedium of “figure out and track which projects need updates”. Fortunately, dedicated long-term readers of this blog (?!) might remember…

my code-review tool

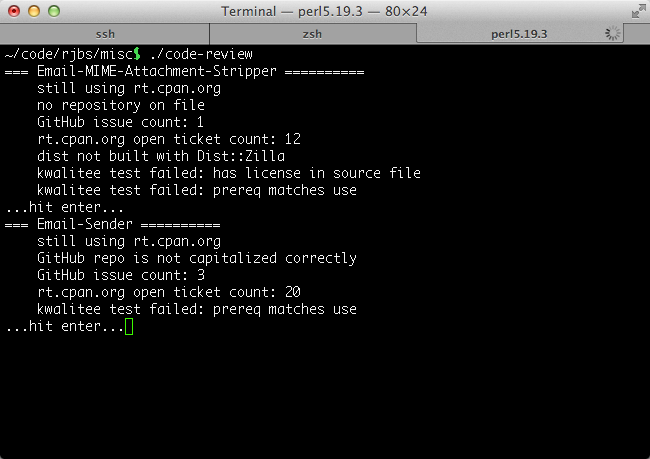

Here’s a screenshot of my code-review program from a 2013 post about how I

keep track of my open source

projects.

I’m not quite as on top of my open source software as I was in 2013, but this tool remains great. In fact, it’s gotten a whole lot better. In that screenshot above, it basically printed out a summary of distributions, in order, and I could hit “Yes, I reviewed” or “No, I skipped” and it would update the last reviewed dates in a YAML file.

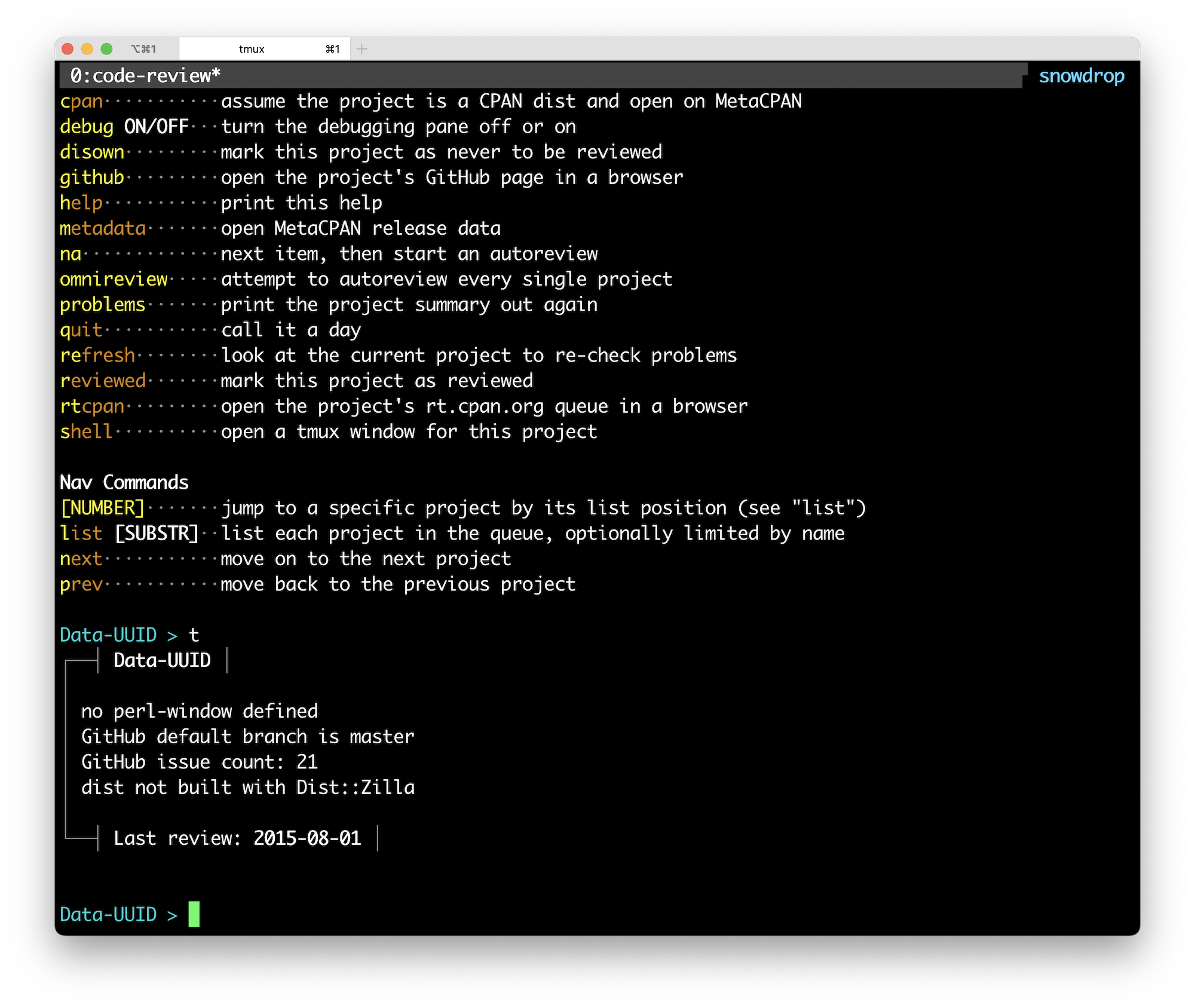

Since then, I turned the whole thing into a captive user interface application using my little CUI application framework, Yakker. Here’s a screenshot of a bit of it:

At the top, you can see help for the commands available. Some of them open

URLs in my browser, taking me to the project on GitHub or CPAN. The shell

command opens a new tmux window with a shell in the repository for the project.

In the lower part of the screenshot, you see the “card” for a project, showing

what problems it’s found. There are a bunch, like “you aren’t using

Dist::Zilla”, or “you have open PRs”. But also included are the problems that

mean I should run my stupid program from above: email address wrong, branch

name wrong, no Perl version policy.

Now the whole thing is very easy:

- fire up

code-review - hit

nto go to the next project until you get to one with just the problems in question - hit

sto open a shell - run

my-stupid-program - look at the diff it commits

- release!

All of this is fairly brainless work, except for #5. Great for doing while you finish watching the second half of the fifth season of Arrested Development. For example.

wrapping up

Anyway, this was … well, I was going to say fun. It wasn’t exactly fun, but I enjoyed doing it. It made me feel like I was in a slightly better place to focus on pieces of my code that could use some more work, rather than stupid chores, because the stupid chores have now all been done. Writing little tools to help clear out that kind of work has always been something I like doing, and writing tools to make writing those tools easier is probably my favorite.

At some point in the not too distant future, I’ll probably write more about Yakker. It’s been a convenient little pile of code, even if it’s still a bit of a mess.

🥂 Happy new year, everybody!