git: rolling it out at pobox and explaining it right

Just over a year ago, I complained about the complexity of Git tutorials found online. My complaint was something like this: /I have no damn idea how Git works, and I’m using it just fine. Stop suggesting that people need to understand how all these things work and just explain the commands./

I stand by this post, but now in a somewhat qualified way. For most of my time using Git, I was using it as a one-user system. I’d commit locally, push and pull to my central remote repository, and that was about it. If I wanted to work with someone, we’d share a single remote to push and pull. I wasn’t quite using it like Subversion, but at best I was using it like SVK.

For people who want to get started using Git, there’s no reason to learn how it all works. Just committing and replicating to a single remote is dead easy, and doesn’t require any serious change of mindset.

In the meantime, I have been learning much more about how git works, mostly for fun, and to do some history rewriting on Pobox repositories before moving them to Git. Still, I thought I had a good handle on how much needed to be explained. I even started work on a somewhat sarcastic set of slides that would reject the “learn how git works before running git init” style of tutorial.

In the last month, I finished converting Pobox to Git. It was a fair amount of work, but most of it was easy and fun. On the first day of work in an “everyone must use git” environment, things went pretty well. I gave a very breif overview of how to commit, push, and pull, and I threw some very simple documentation and flowcharts on our internal wiki.

Two weeks later, it was clear that this was not enough. I was actually very happy with how things went, but without more explanation, I knew that things would not get better on their own. Actually, thinking back on it, I’m reminded of a professor who once told me, “Don’t worry. Even though you’re failing every test, I think you’re on your way toward a B+.” Everyone kept having problems, but they were problems that could be overcome, and many of which were the result of the workflow I’d originally chosen for us.

Like Perl, Git has a very “There’s more than one way to do it!” attitude. You can roll out Git in many ways, depending on your personal needs or your company’s needs. I had chosen poorly – at least with respect to the kinds of discipline I expected to be used when merging.

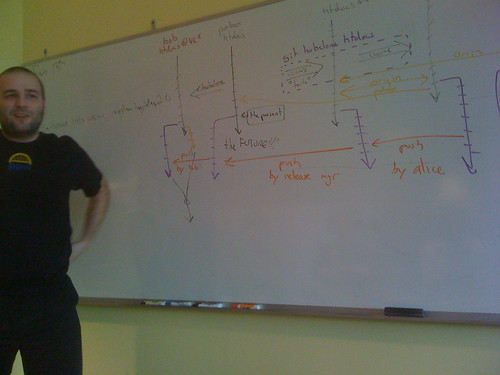

Friday, I tried again: I got up and explained more about how merging works, what push and pull requests do, and how remotes are used to share changes. I drew all the box and arrow diagrams that I thought I could avoid, originally.

It seemed to go pretty well. Despite a few blasphemous interjections and remarks about glassy eyes, I actually think it managed to explain the basics needed to understand a simple collaborative DVCS workflow without getting too far into anything unrelated or overly technical. I’m hoping that two weeks from now, we’ll just be coasting along, smoothly sailing.

My sole concerns, now, remain with a few features that GitHub is lacking. For the most part, GitHub is a great product for outsourcing repository hosting, but its private repositories do not allow read-only access, which makes certain operations very dangerous. For example, I expect this error to come up now and then:

alice$ git remote add rjbs git@github.com:rjbs/pobox-mailredactor.git

alice$ git fetch rjbs

alice$ git checkout -b new-algo rjbs/new-algo

alice$ vi bin/program

alice$ git commit -a -m 'added new shared secrets'

alice$ git push

Alice may expect this to push back to her repository, because that’s what git

would do in her master branch. Unfortunately, git will try to push back to the

remote branch she’s tracking – in this case, rjbs/new-algo. Because GitHub

doesn’t allow read-only access, she will be trying to stomp my changes. It

would be nice to get a reminder that “you tried to push to rjbs/new-algo, but

permission was denied.”

Even better, .git/config could indicate separate remotes for pull and push.

Push could go back to origin, but pull could pull from the tracked remote.

I’ve already written one git command, git-hubclone, that forks on GitHub and

then clones that and adds useful remotes. I will probably write others to

better encapsulate our workflow as time goes on.

In the end, I’m very happy with our cutover to Git. It went well, and I’m already reaping the benefits. I look forward to much, much more branching in our future.